Photos and Text by Jim Bland. All Rights Reserved.

This spring I set out to photograph all three North American teal species. All overwinter here in Los Angeles. Each is a beautiful, spunky little species of duck. All inhabit shallow marshes and sloughs where there is an abundance of emergent and fringe vegetation (cattails and tules). Their customary overwinter sites around Los Angeles can be found by exploring eBird at www.ebird.com/explore. The teals were long considered very closely related, but recent genetic studies indicate the Cinnamon and Blue-winged Teals are more closely related to the Northern Shoveler (genus Spatula), whereas the Green-winged Teal is more closely related to the Northern Pintail (genus Anus). Hunters prize teals for their fast and erratic flight and sweet and tender meat. It is fitting that my first social-media-linked photo essay is on waterfowl. No doubt, I will frequently extol the virtues of Los Angeles for wintertime waterfowl portraiture. If you’re looking for huge flocks of migrating waterfowl you’ll need to look elsewhere, but LA’s urban wetlands are fantastic for getting close, largely because the birds are habituated to frequent nearby human activity.

Cinnamon Teal. Having spent my youth tromping the wetlands of California’s San Joaquin Valley, I'm quite familiar with the Cinnamon Teal. It's one of just a handful of duck species that breed in abundance on the valley floor. The Cinnamon Teal's continental range extends from southern Canada to southern Mexico but, unlike the other teal species, it occurs only west of the Mississippi River. In California it breeds across much of the state, but overwinters primarily in the central and southern coastal regions. In spring, males are extremely attentive to their mates. If a female climbs onto a log to preen, the male will join her; when she returns to the water the male will follow close behind. Breeding males communicate with a chattering "gredek ... gredek" while pumping their heads up and down. The call sounds vaguely like the call of a tree frog. All teals are voracious feeders; filtering muck at the edge or bottom of shallow ponds with comb-like "lamellae" that rim their mouths and tongue. One of the challenges in photographing teals is to catch a moment when they don't have their faces half submerged in pursuit of food. Patient observation reveals that they haul up onto a log or rock every half hour or so in order to dry out and prepare their feathers for another round of drenching. I took advantage of this behavior to set up for photography. I found a spot where nearly everything was right: teals were usually present, the angle of morning sunlight was ideal, and there was existing cover at just the right distance to obscure my pocket blind. But there was only open water surrounded by a wall of tules, so the birds only foraged and never rested or preened there. So I gathered two dead willow branches from nearby and anchored them exactly where I wanted the birds to perch. Within 30 minutes teal were perching on them. "If you build it, they will come"!

Green-winged Teal. The Green-winged Teal breeds throughout the northern U.S. and Canada, and winters in the southern tier of states and Mexico. In California it breeds only in the far northeast corner of the state. Elsewhere in the California it occurs only during migration, primarily in September through March. Its arrival in Southern California in September is relatively early among southbound migratory birds. In flight, flocks of Green-winged Teal characteristically bob and weave. The call of the male is a ringing "krick" whistle that's uttered year-round. It's not uncommon to find all three teal species overwintering side-by-side on southern California's larger marshes. But comparatively speaking the Green-winged Teal prefers larger, more open bodies of water. The species tends to be more timid than Cinnamon Teal, so given its preference for open habitats it can be more challenging to get close enough to photograph. I've gotten my best shots by setting up a blind at a spot I know they like and waiting patiently for them to return. I have no problem spending time in blinds. As a wildlife researcher I've frequently lived in observation blinds - there's always something going on in nature to observe.

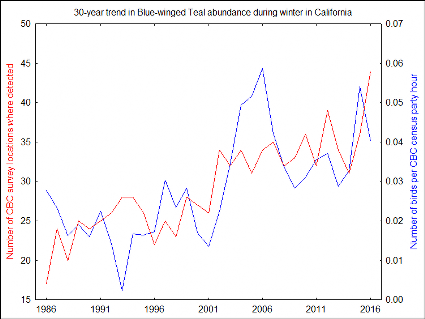

Blue-winged Teal. The Blue-winged Teal breeds throughout the northern U.S. and Canada and winters primarily in Central America. In the U.S., its winter range hugs the southern coasts. In California it's uncommon and spottily-distributed, and breeds in small numbers only in the far northeastern counties. I have found it equally at home in open or densely-vegetated marshes. I've observed it making more use of tidal marshes and sloughs than other teal species. The male's call differs considerably from the frog-like "gredek" the Cinnamon Teal and police-whistle-like "krick" of the Green-winged Teal. It's whistled "pwis" is more like the voice of a shorebird ("peep" in birdwatcher parlance) than that of a duck. The female voice of all three teal species, by the way, is a nasally toy-like quack or series of quacks. Females are difficult to distinguish from female Cinnamon Teal. In the images above you'll see that the white patch at the base of the female Blue-winged's bill is lacking on the Cinnamon Teal. I’ve always yearned to get better acquainted with this beautiful little duck. Much to my delight, in recent decades it has become increasingly common in Central and Southern California during migration and in winter. A quick analysis I conducted on historical Christmas Bird Count Data (National Audubon Society, www.christmasbirdcount.org) indicates wintertime abundance has increased 2- to 5-fold in California over the past 30 years. Now that I'm familiar with its haunts and ways in Southern California, I look forward to metting it eye-to-eye for many winters to come.